MNRE has expanded scope of the ALMM policy by bringing open access and rooftop solar projects under its purview. As per an order released last week, all open access and net-metering based projects applying for approval from 1 April 2022 onwards may procure only modules approved under ALMM policy.

- The ambiguous order has created confusion in the already struggling distributed renewables market;

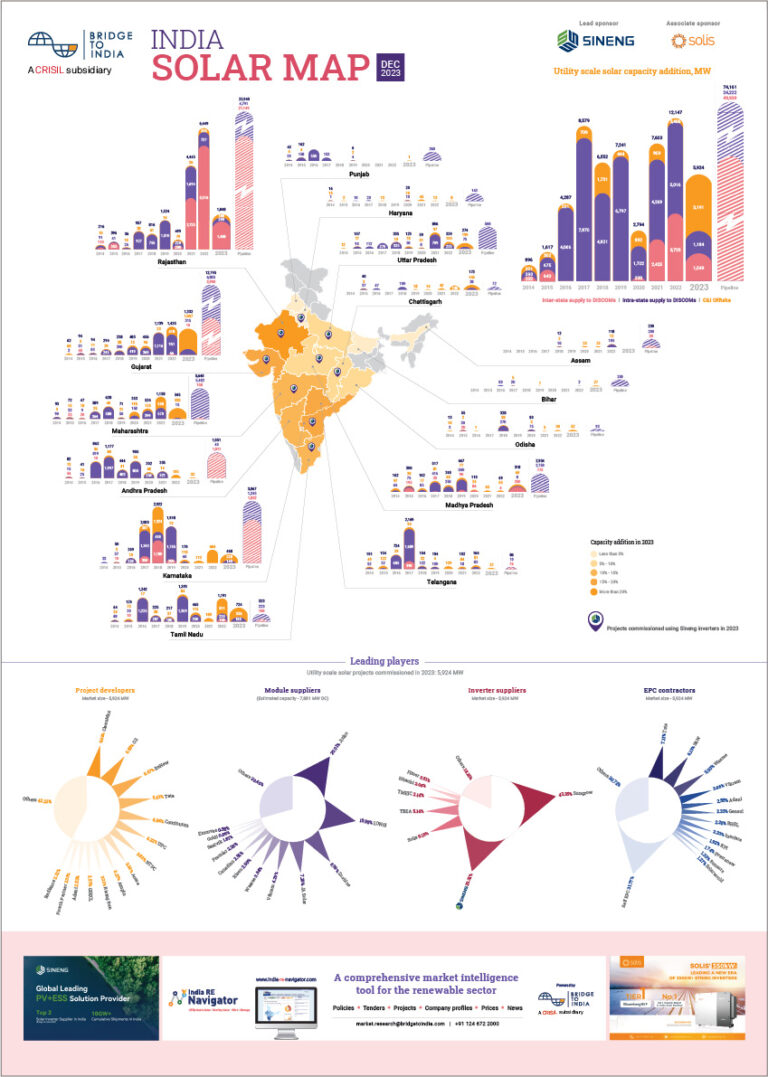

- So far, MNRE has approved only 10.9 GW of module manufacturing capacity and nil cell manufacturing capacity under the policy;

- ALMM is a flawed policy concept as it restricts competition, promotes inefficiency and increases costs for consumers;

MNRE has clarified in the past that only Indian manufacturers would be approved under ALMM. But utility scale solar projects bid before 9 March 2021 – 42,491 MW of pipeline – would continue to import modules as they are exempt from both ALMM and BCD. The policy scope has therefore been widened to open a new demand source for domestically manufactured modules.

There are, however, some major discrepancies in the MNRE order. The meaning of “apply for open access” is not clear since open access projects require multiple approvals from different agencies. The lead time of 2.5 months given to such projects is also inadequate as some projects may have already procured, or be in advanced stage of procuring, modules particularly as the Basic Customs Duty is expected to kick in on all imports from April 2022 onwards. Finally, rooftop solar systems are installed in many alternative configurations (gross metering, net billing, or non-grid connected) without net metering benefit. Exclusion of such systems from policy coverage seems to be an oversight. The MNRE order has left a trail of confusion and we expect to see a series of amendments and clarifications in the coming months.

There is another fundamental issue with the new order. So far, MNRE has approved 38 module manufacturers with total manufacturing capacity of 10.9 GW under the ALMM policy. No cell manufacturing capacity has been approved yet. In any case, total estimated domestic cell manufacturing capacity of 3.5 GW is highly insufficient to meet market demand. Commencement of commercial operations by new cell and module manufacturers is expected to take minimum 2-3 years. It is therefore not possible for project developers to comply with the ALMM policy during this period.

Table: Approved module manufacturers under ALMM policy

Source: BRIDGE TO INDIA research

The government has already undertaken a series of measures to promote domestic manufacturing – BCD, domestic content requirement for PSUs, agricultural solar and residential rooftop solar, Production Linked Incentives, manufacturing-linked project development tender, and tax rebates. In the backdrop of such extensive multi-faceted support, the ALMM policy is irrelevant. Moreover, the government’s intent to deny approvals to foreign manufacturers or creation of a walled garden, is akin to a tax on consumers. It restricts competition, promotes inefficiency and increases costs for consumers. If the policy continues to be implemented in its current form, it also runs the risk of international trade litigation and retaliatory measures by other countries.