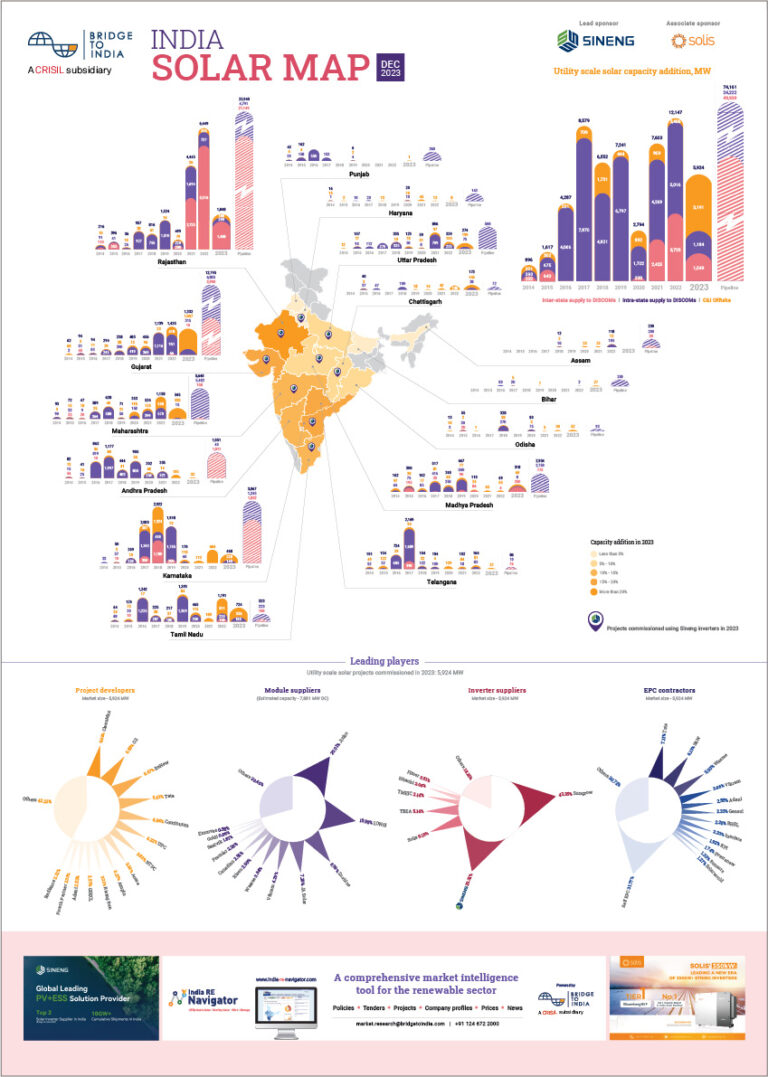

MNRE has revived offshore wind plans with industry consultation for developing 1 GW and 2 GW capacity off the coast of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu respectively. Power is proposed to be sold to the respective states at a fixed tariff of about INR 3.50/ kWh with SECI as an intermediary offtaker. MNRE aims to award total capital subsidy of up to INR 140 billion (USD 1.8 billion) to project developers through a competitive bidding process. It is proposing to complete bidding process for the first 1 GW project this year with expected commissioning date of 2025. The second tranche of 2 GW capacity in Tamil Nadu is expected to be tendered out in 2024. Overall, the government is aiming to issue tenders for 30 GW capacity by 2030.

It is worth recalling that offshore wind has so far failed to take off since states are unwilling to buy expensive power – expected LCOE of about INR 9.00/ kWh – and the central government has refused to bear the substantial subsidy burden. MNRE had announced the offshore wind policy in 2015 with a target of developing 5 GW capacity by 2022. Preliminary wind resource assessment, environmental impact assessment, geophysical and geotechnical studies were completed for a 1 GW pilot project off the Gujarat coast in 2018 with financial and technical assistance from the European Union. But the project never took off because of economic challenges.

MNRE seems more keen this time possibly because of acute execution challenges faced by onshore wind (note to follow next week) and sharp fall in offshore wind cost (see figure below). It is also more hopeful of the Finance Ministry’s support after getting support for expansion of the solar PLI scheme.

Growth led by Europe and China

Total global offshore wind capacity is currently estimated at 55,678 MW. China has leapfrogged other countries by installing a mammoth 17 GW capacity in 2021 ahead of its USD 134/ MWh (INR 10.20/ kWh) feed-in-tariff expiry date. Other leading nations including the UK (total installed capacity of 12,700 MW), Germany (7,747 MW) and the Netherlands (2,460 MW) have also relied on feed-in-tariffs and other subsidies to kick-start the market. The USA, Denmark, France, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan are planning significant offshore wind development in near future.

Figure 1: Annual capacity addition, MW

Source: IRENA

Developed nations prefer offshore wind mainly as they run out of suitable onshore sites due to complex planning laws and resistance from local populations.

Improving techno-commercial viability

With improvement in technology, scale and increase in turbine sizes (up to 16 MW each), capital cost and LCOE have declined by about 50% since 2016, but are still relatively steep at about USD 2 million/ MW and USD 0.10-0.12/ kWh respectively in the Indian context.

Figure 2: Offshore wind LCOE in other countries, USD/ MWh

Source: U.S. Department of Energy

Weak case for offshore wind in India.

We believe that the government plan to tender 30 GW capacity by 2030 is too ambitious to be realistic. DISCOM appetite is likely to be nil in absence of central government subsidies. Moreover, gestation period for first few projects is likely to stretch to over five years since requisite infrastructure and manufacturing capacity is not available in India.

Given the substantial subsidy burden and lack of domestic manufacturing capacity, a robust debate is needed on future of offshore wind in India. Certainly, there is no scarcity of suitable onshore sites in India unlike in more developed nations. Use of government funds would be significantly more beneficial in accelerating build out of storage and transmission capacity.