The Indian government’s revised deadline for providing universal electricity access to all households under the SAUBHAGYA scheme lapsed on 31 December, 2018. The scheme portal shows that 24 million households, 97% of the revised target, have been electrified since October 2017. The only states yet to achieve 100% electrification – Rajasthan (current status 98%), Chhattisgarh (99.6%), Assam (95%) and Meghalaya (83%).

- SAUBHAGYA and ‘power for all’ have the potential to boost power demand by 3-5% in the short-term and much more in the long-term;

- Universal availability of power can create a virtuous growth cycle and attract more investments into the sector;

- Insulating DISCOMs from political pressure to make them financially sustainable is the key to longer-term reform of the sector;

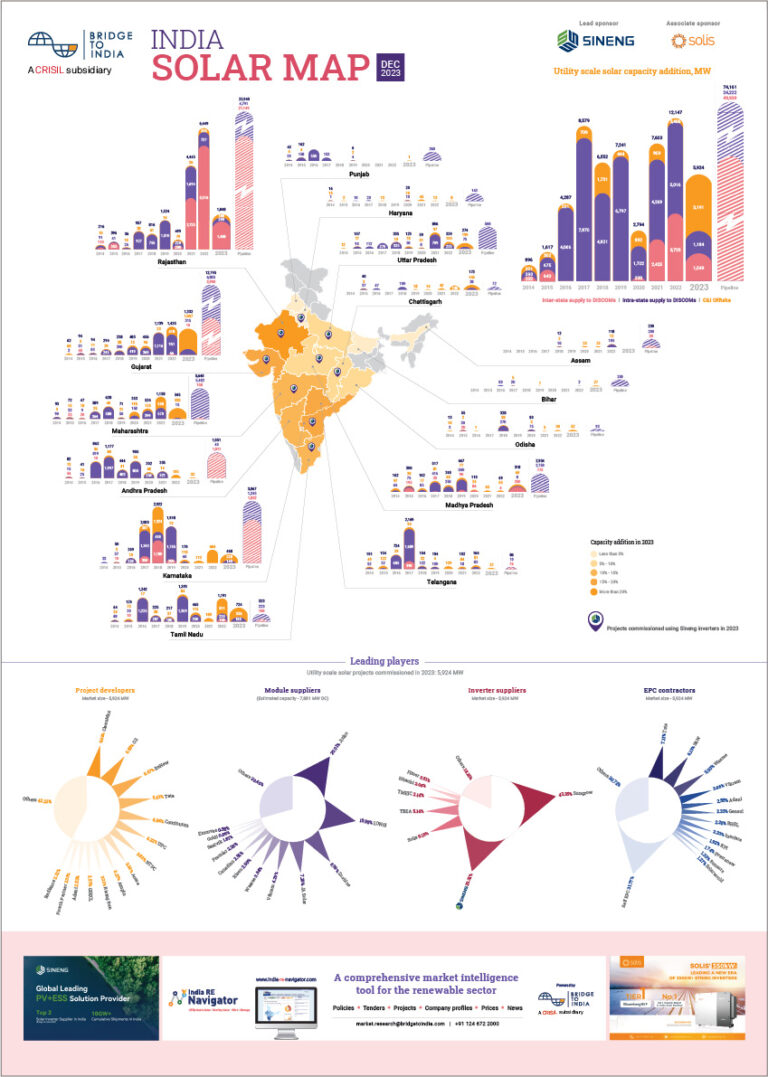

The progress, notwithstanding minor slippages, is impressive. It is a crucial milestone for the power sector in India. If the government is serious about the proposals to provide 24×7 power and penalise DISCOMs for any failure to do so, it can bring about a radical transformation in the sector. We have already seen a notable uplift in power demand this year, which in the absence of major upturn in industrial activity points to success of SAUBHAGYA. The increase seems due as much to new connections as to a gradual decline in load shedding in the past 2 years.

Figure: Power demand growth, GW

Source: CEA, Ministry of Power

Universal availability of power has immense potential to drive socio-economic growth and creating a strong virtuous growth cycle. And it is critical for overall revival of the sector in many respects. Better utilisation of existing assets, many of which remain stranded because of lack of PPAs, would mean improvement in asset returns and bank balance-sheets. It also means higher demand for renewable power. As demand increases (and prices go up as a result), more investment capital is bound to flow into the sector.

But there is the inevitable question – how much of this progress is sustainable? Can rural and residential consumers really expect 24×7 power on a long-term basis? There is certainly some historic evidence that power ‘demand’ goes up in five-yearly cycles in advance of the general elections. DISCOMs have little incentive to supply power to rural and marginal residential customers as their tariffs are extremely low. At the same time, cost to serve these consumers is relatively high because of high T&D losses and poor collections.

For SAUBHAGYA benefits to endure and become permanent, we need genuine reform of the power sector – separation of ‘content’ and ‘carriage,’ insulation of DISCOMs from tariff subsidies and tariff rationalisation – but that seems a distant prospect yet.