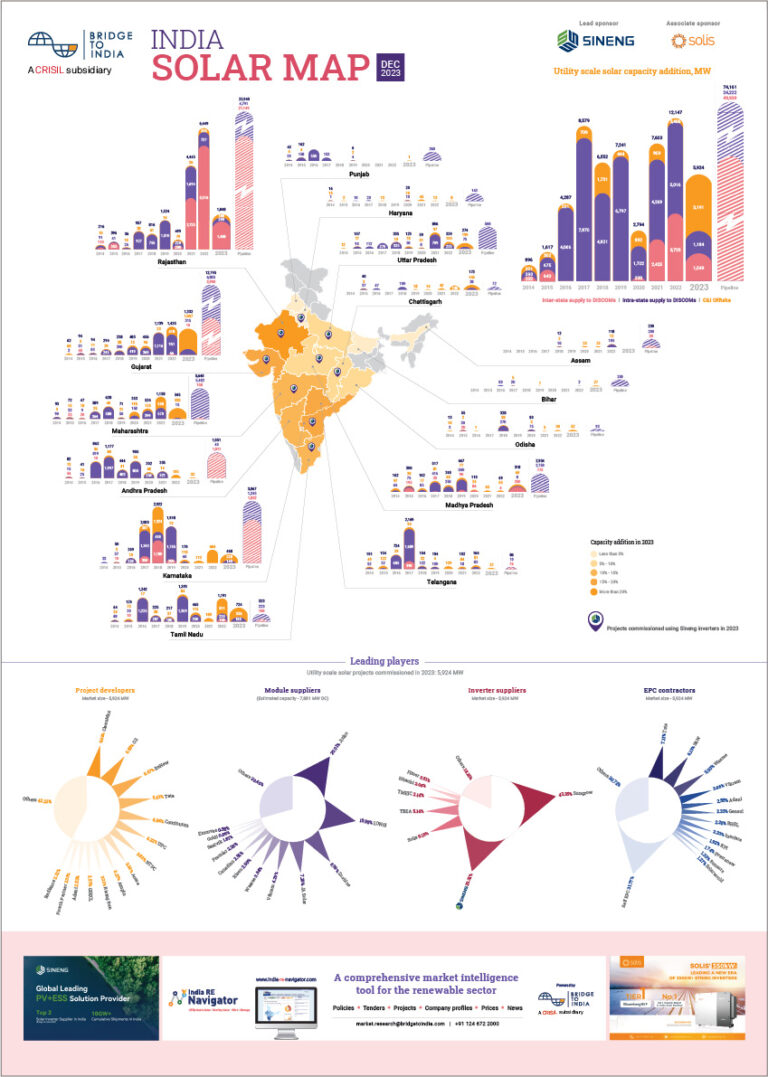

Total pipeline of utility scale solar and wind projects has reached a near all-time high of 32.1 GW. After a relatively lull FY 2018-19 when only 6,174 MW was installed (down 43% over previous months), installation activity should be expected to boom over the next 24 months. As per our database, based purely on commissioning schedules specified under the tenders, India should add 17.8 and 13.8 GW of total solar and wind capacity in 2019 and 2020 respectively. However, sharp deterioration in debt financing environment is threatening to disrupt this positive outlook. Both availability of debt and cost have become significantly tighter because of drying up of liquidity in the debt market.

Figure: Scheduled commissioning timeline for solar, wind and hybrid projects

Source: BRIDGE TO INDIA research

There are several exogenous reasons for the current situation. After the IL&FS financial crisis late last year, the non-banking financing companies (NBFCs) – a crucial source of debt finance for the renewable sector – have been hit hard by lack of liquidity. Commercial banks, their most common source of funding, have closed the taps. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been tightening lending and risk norms. The private NBFCs have almost shut down for new business while the public sector ones are more cautious. Merger of the two government owned NBFC giants, PFC and REC, has also contributed to the slowdown.

India’s relatively new insolvency law, mandated to clean up bank balance sheets, improve ease of doing business and implementation of the bankruptcy code has further sent banks in a spin. The prospect of recognising losses on almost INR 12 trillion (USD 170 billion) of bad assets is scaring them. The messy state of power sector is not helping. Thermal power is believed to account for a significant chunk of bad assets. Lenders are spooked by worsening DISCOM financial position and constant talk of renegotiation by state governments.

Consequently, cost of debt has risen by as much as 1.5-2.0% to 11.00-11.50% per annum putting financial viability of most projects at risk. But more importantly, there is a serious question mark over availability of debt funding and installation timelines. We understand that some lenders are completely refusing to lend to projects with direct DISCOM or state government exposure. They prefer projects where offtake risk is intermediated by central government owned NTPC or SECI.

There are two silver linings here. One, the pipeline is highly concentrated as the smaller players have been squeezed out by falling returns, growing execution challenges and increasing project sizes. Top developers are generally strongly capitalised. They should be better placed to raise funding through short-term resources, access to capital markets and corporate resources. Two, the macro-economic environment is expected to improve post-elections. There are expectations of aggressive rate cuts by RBI as well as a strengthening Rupee, both of which could help ease the crunch.

Figure: Share of top renewable developers

Source: BRIDGE TO INDIA research