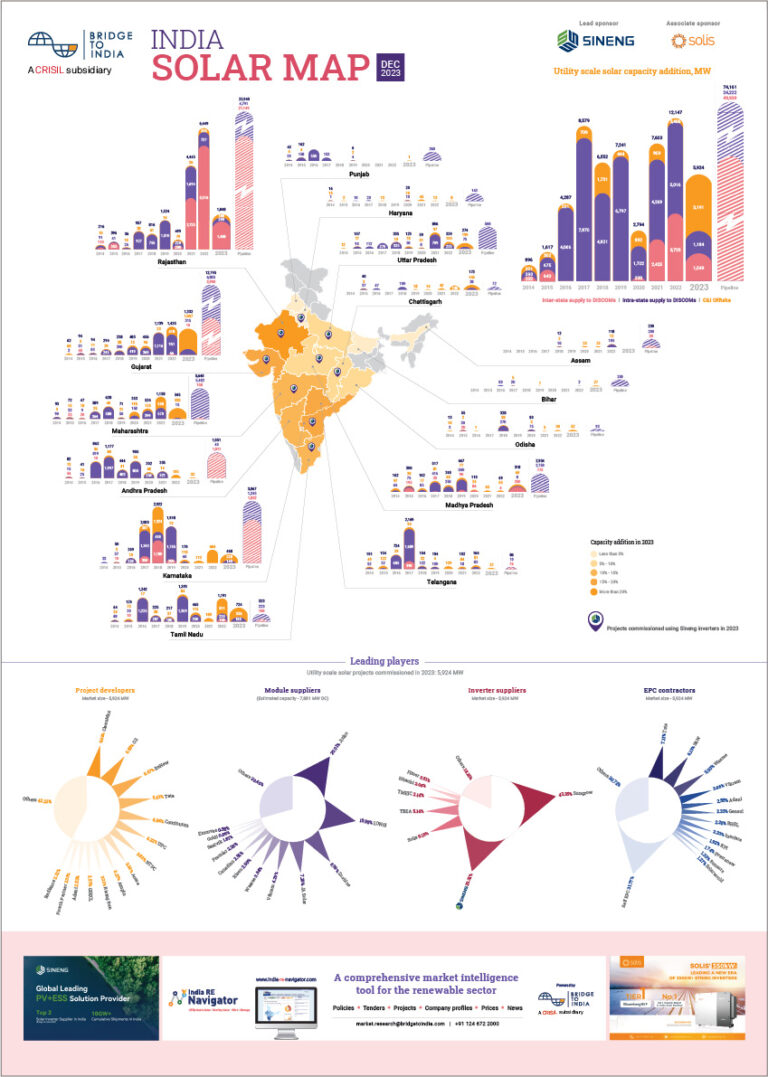

As things stand today, safeguard duty (SGD) of 14.5% on solar PV cells and modules is set to expire on 29 July 2021. While the Ministry of Commerce trade investigation is still supposedly ongoing, another extension is looking unlikely. Basic customs duty (BCD) of 25% and 40% on cell and module imports respectively is set to kick in from April 2022 onwards. We are now therefore looking at the possibility of an eight-month duty free window from 30 July 2021 to 31 March 2022.

- The duty-free window would offer relief to project developers with substantial project pipeline coming up for implementation;

- Constrained supply from China and high module prices in H2/ 2021 are potential spoilers;

- The industry faces a tough choice – import modules duty free at higher cost or wait until prices soften next year and deal with tedious ‘change in law’ claims;

The duty-free window is meant to be a little concession to project developers ahead of the steep duty looming ahead. The industry is wary of duty burden for substantial solar project pipeline – 26.6 GW as of December 2020 (setting aside about 18 GW of auctioned projects with unsigned PPAs) – coming up for implementation. While most of this pipeline enjoys ‘change in law’ protection, the settlement process is messy, time taking and financially onerous for DISCOMs. The government is also mindful that domestic manufacturers do not have sufficient capacity to cater to this demand.

Figure: Import duty timeline

Source: BRIDGE TO INDIA research

The duty-free window should logically lead to a huge import surge. Both developers and end consumers, particularly C&I consumers, would accelerate project tables and bring demand forward to avoid duty burden. Similar policy-linked windows have led to major one-off surges in capacity addition in the US, Europe and Vietnam, amongst other countries. But we expect the effect in India to be somewhat muted for multiple reasons. With COVID flaring across the country, tremendous uncertainty lies ahead on pace of contract execution, financial closures and site activity. Large, well-capitalised developers like Adani, ReNew, Tata, Azure and Ayana have the financial capacity to stockpile modules but we believe that they would look to bring only 50-70% of their demand forward both to spread financial burden and physical execution.

The other problem is rising module prices and constrained supply from China particularly in H2/ 2021. Mono-crystalline module prices have been firming up now for five months and are expected to stay in the USD 0.23-0.24/ W range for the whole year because of soaring input costs and strong global demand, expected to touch a record 180 GWp this year.

The price sensitive Indian market faces a tough choice – import modules duty free at higher cost before March 2022 or wait until prices soften next year and deal with tedious ‘change in law’ claims. We expect total potential import demand at around 20 GW through March 2022 but only about 60% of this may be fulfilled because of various constraints.