Chinese module major Trina launched a new series of 550 W bifacial modules recently and announced production of a new 600 W version from next year onwards. The company also announced that it expects to triple production to 31 GW in 2022, up from 10 GW last year. The new modules use half-cut cells and are reported to have efficiency of over 21%. The company’s peers including LONGi, Jinko, Canadian Solar, JA Solar and Risen have announced broadly similar breath-taking jumps in technology and production scale.

- Leading Chinese manufacturers are upgrading technology and investing aggressively in R&D and capacity expansion;

- Uptake of new technologies by Indian IPPs is increasing due to affordable prices;

- The government policy comprising mainly trade barriers and capital subsidies is not equipped to improve fundamental competitiveness of manufacturing;

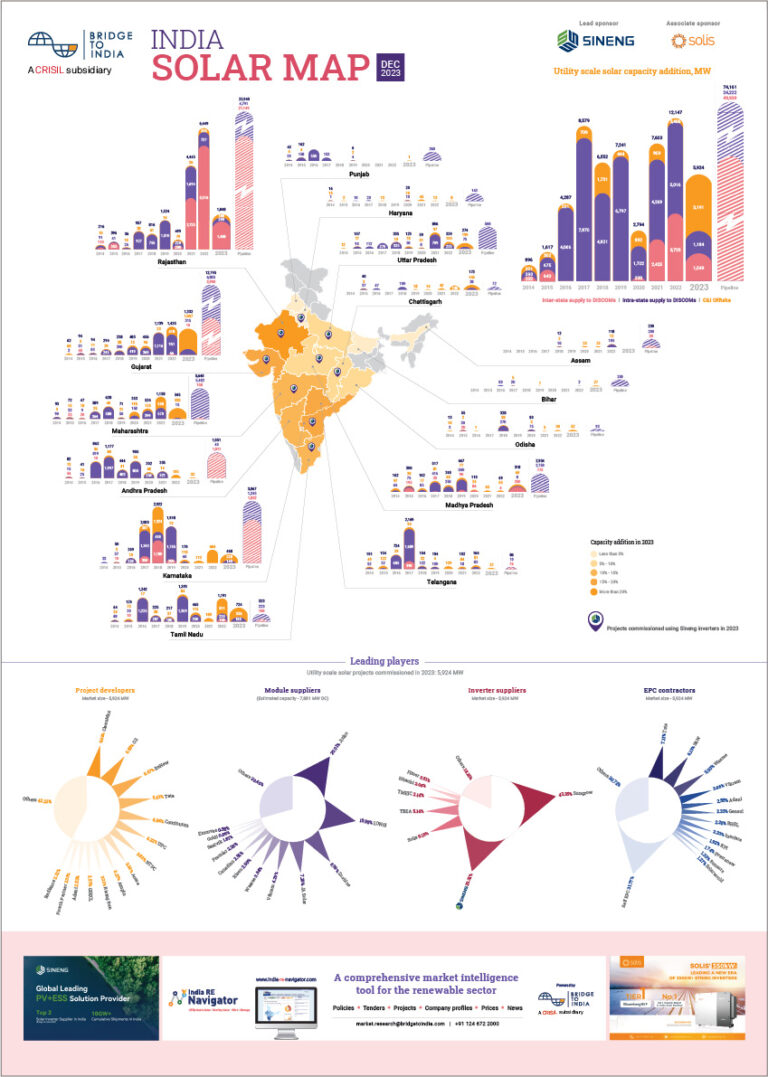

Leading Chinese module manufacturers continue to rapidly upgrade technology and are making huge investments in R&D and capacity expansion. The Chinese government is weighing in with a new set of proposed guidelines, issued in June 2020, for module manufacturers to improve focus on advanced technologies and lower production cost. These developments have critical implications for the entire solar value chain. One, prices have crashed by 15% already this year. Mono-PERC and bifacial technologies are becoming mainstream as price differential over multi-crystalline modules has narrowed to less than USD 1 cent and 2 cents respectively (see figure). Two, the smaller manufacturers, not just in other countries but even in China are getting left behind. Most tier 2 and tier 3 manufacturers in China – lacking in technology, scale and access to international markets – are facing increasing financial stress and risk being squeezed out of the market. Share of top ten module makers worldwide (eight from China) is expected to touch a record high of 70% this year.

Figure: PV cell capacity by technology, MW

Source: PV Infolink

Three, the IPPs face a more complex choice both for module technology and suppliers. Downward pressure on LCOE is forcing them to adopt new technologies but often with limited proven track record.

In India, uptake of new technologies has been relatively slow because of high prices in the past. But with LCOE gains exceeding price differentials, bulk of new projects are now using mono-PERC modules. We expect bifacial modules to become mainstream by 2022.

Meanwhile, the government has been struggling even to implement quality assurance guidelines. Deadlines for BIS and ALMM initiatives are being progressively extended because of lack of technical infrastructure. It is a sobering thought that in such an environment and against fierce competition from Chinese manufacturers, how are Indian manufacturers going to compete? The government policy, directed mainly towards creating trade barriers and providing capital subsidies, is not equipped to improve fundamental competitiveness of manufacturing. Even the extension of safeguard duty by one year is a worthless exercise. So long as Indian manufacturers are unable to compete with their Chinese counterparts on scale and technology, the goals of energy security and self-sufficiency would remain elusive.