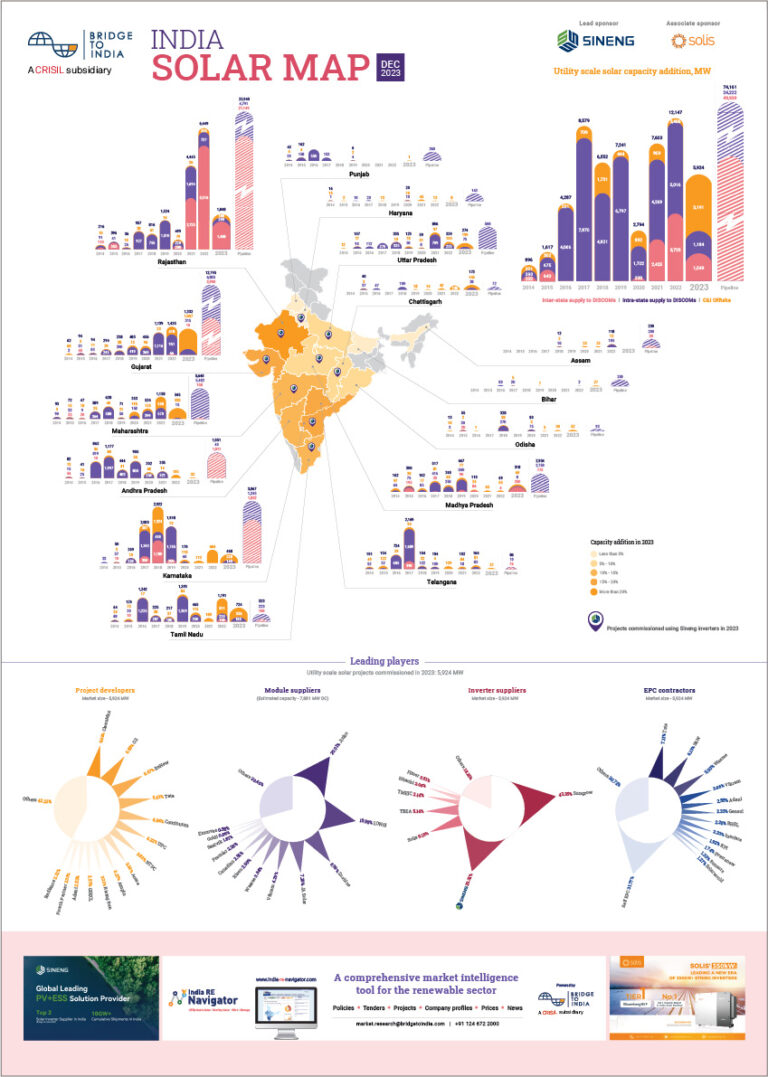

WRITTEN BY OLIVER HERZOG & DORJE WULF – QUO VADIS, INDIA SERIES 1/4

The Euro-crisis has further sensitized investors for sovereign debt levels in the wake of slowing economic growth. As one of the most promising emerging markets following China, India has witnessed a string of negative macroeconomic news recently:

- Real GDP growth slowed to 5.3% in the fourth quarter (ending March 2012) of 2011 the lowest rate in 9 years

- Quarter over quarter gross fixed capital formation has fallen ever since the beginning of 2009 in every consecutive period

- Overall budget deficit (including states and off-balance sheet items) is expected to approach 9% this year

- Gross public debt is expected to reach 68% of GDP in 2012

In the wake of the Euro-crisis, slowing economic growth in emerging markets has caught the attention of investors. Deemed as the new rising star following China, India s current state of economy has particularly raised concerns. But recently, there have been several worrying developments in terms of newly proposed legislature, which might seriously alienate investors. No doubt, India has tremendous growth potential but political action is needed urgently as reforms seem to have reached a dead end. It is now on Indian politics to prove that the great optimism investors and business executives have shown towards India for so long was not a mistake.

While the economy grew at an average of 9% annually for five straight years up to 2007 (IMF, 2012), India now seems to have fallen into a second slump since the inception of the financial crisis. In part driven by high oil prices and weakening external demand, GDP grew only by 5.3 percent in the fourth quarter (ending March 2012) of 2011 the lowest rate in nine years and way below IMF expectations. While this figure is still impressive, for an economy with a population of 1.2 bn this is not enough to alleviate India s masses (around 30% live below the line of poverty) from poverty within a satisfactory time frame. Ten million young Indians enter the labor market every year clearly, growth is needed to create these jobs. By the same token, India would need an annual growth of at least 6% to maintain financial stability. Lower growth rates will increase the weight of India s debt burden and can lead to a dangerous debt spiral. Greece is an illustrative example how high debts increase the cost of further borrowing. In order to drive down these costs, the government has to cut spending and increase taxes which both have a negative impact on growth. Lower growth rates again mean lower government tax income which makes it even harder to repay the debt.

In India, excessive public borrowing and high inflation, which has been close to 10% for a couple of years now, have led to high costs of debt financing. Furthermore, legal limits on foreign activities in sectors such as multi-brand retail, pharmaceuticals, pensions and insurance have deterred Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs). Several attempts for reform in this field have been blocked by the ruling Congress party s coalition partners, such as the Trinamool Congress. Taken together, high private sector interest rates and procedural obstacles such as land purchase and policy uncertainties have resulted in disappointing industrial investments. Ever since the beginning of 2009, quarter-over-quarter investments (gross fixed capital formation) have fallen in every consecutive period from 32% of GDP to around 28% in the third quarter of 2011. Investors have been further discouraged by governmental arbitrariness like the levying of retrospective taxes on companies (see the Vodafone case as an example). The 2012 World Bank Doing-Business ranking (132 out of 183) indicates that India s legal business environment needs to be improved with particular focus on contract enforcement and investor protection which deteriorated recently.

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor Data

With an expected overall fiscal deficit (including the states and off-balance sheet items) of 8.5% in 2012 and gross public debt of around 68% of GDP, the government will find it hard to revive growth through fiscal measures. Consequently, Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee announced that taxes will be raised and subsidies for fuel and food are to be cut. At the same time, the defense budget of the world s largest arms importer is expected to increase by 17% this year. With little fiscal leeway and monetary policy strained by stubborn inflation, the only way to get back to a higher growth path will be structural reforms. India still has some way to go to become the number one destination for global investors, as announced by Mr. Anand Sharma, India s Minister in charge of Commerce, Industry and Textiles at a recent visit in Hamburg.

READ THE NEXT PART OF OUR QUO VADIS, INDIA SERIES about “Fragile political environment & darkening investment climate soon.