In the past few months, there have been multiple reported instances of Chinese module suppliers renegotiating prices and/ or cancelling orders. Mono-crystalline module prices have surged to USD cents 25/W on a CIF basis (before domestic duties and taxes), a rise of 39% in the last year, on the back of rising input costs.

- Spike in polysilicon prices explains most of the recent price increase;

- The Chinese manufacturers have been cutting back production rather than accepting lower margins unlike in previous market cycles;

- With entire solar value chain expected to become supply side surplus by mid-2022, prices should start falling by middle of next year;

There are two fundamental reasons leading to the jump in prices. The major contributor is a spike in polysilicon and other commodity costs including aluminium, silver and glass in response to global economic recovery. Polysilicon prices, in particular, have jumped by a staggering 4.4x in the last year after a series of disruptions owing to floods, fires and other outages at various factories.

The other contributor to higher prices is increasing consolidation in the module manufacturing business and the changed outlook of leading module suppliers on volumes vs profits. Top 10 suppliers now command 80% market share, up from 47% just five years ago due to aggressive investments in technology upgradation and capacity expansion. The suppliers, already suffering from low margins, have chosen to cut back production rather than accept a reduction in margins. Capacity utilisation for some players in H1 2021 is believed to have fallen to a low of 30-40%. The new practice has even led to accusations of cartelisation against the suppliers.

While market consolidation is expected to carry on, there is relief coming up on the input cost front. Glass prices have already fallen to the lowest levels in recent years as Chinese glass manufacturing capacity has jumped from 28,000 tons/ day last year to an estimated 46,000 tons/ day this year. Polysilicon prices are similarly expected to start coming down from H2 2022 onwards due to huge expansion plans in advanced stages – capacity is expected to grow by more than 2.0x times to 1.5 million tons per annum in the next two years. Downstream cell and module capacity is already well in excess of demand at about 350 GW (2021 demand estimate: 160 GW).

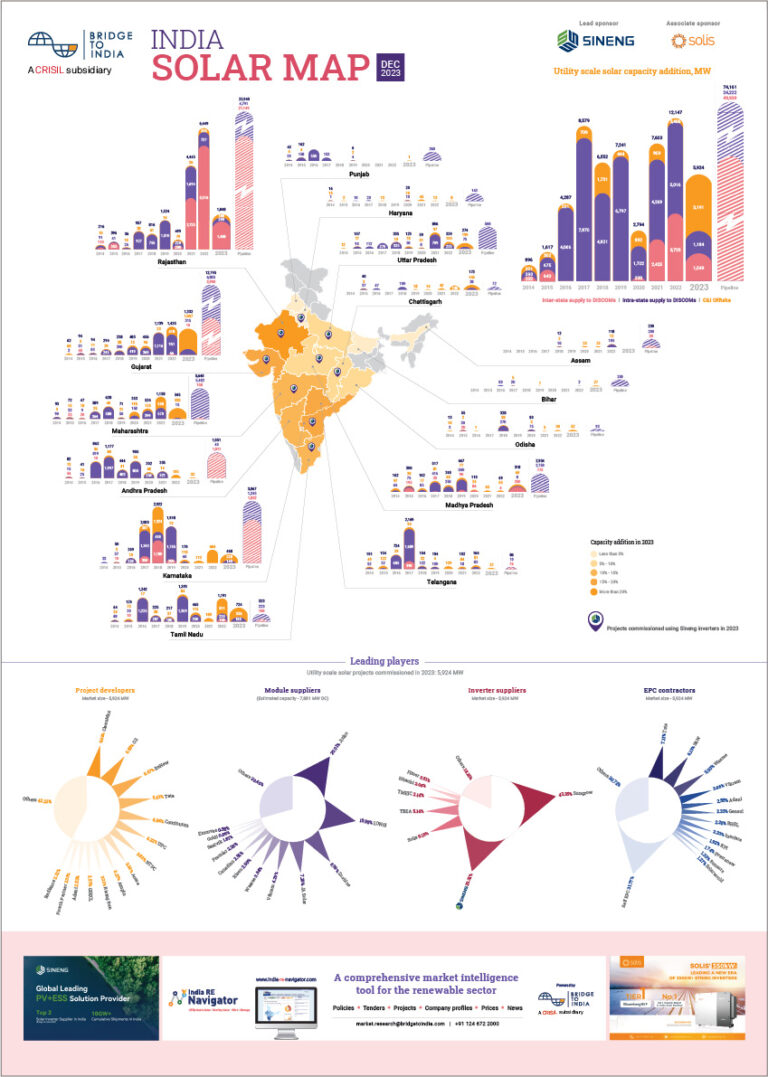

Figure: Relative movement in polysilicon, PV glass and aluminium prices

Source: PV Infolink, BRIDGE TO INDIA research

Even if global demand stays strong, entire solar value chain is expected to have surplus capacity by middle of 2022. Prices should therefore start softening next year. However, a sharp fall, as witnessed in 2018 and 2020, seems unlikely due to higher concentration in the industry. We expect prices to fall more gradually to around USD 20 cents/ W levels by end 2022.

For the Indian market, the implications are not savoury. There is a substantial pipeline of about 30 GWp, reliant on imports, over the next two years. This pipeline is unaffected by ALMM and is also entitled to ‘change in law’ compensation for basic customs duty (BCD). The developers face a tough choice – import modules at higher prices now, or wait for prices to fall next year and deal with BCD risk and delay penalties.