Last three months have seen frantic activity in the renewable energy sector. Many new policies – SRISTI and KUSUM, FAME, storage, ALMM – and tenders aggregating 30 GW were rushed in the last quarter but we now have a relatively quiet six week period until the last votes are cast on 19 May 2019. We will use this period to take stock of this government’s track record.

Arguably, the single biggest achievement of the BJP government has been to upscale the 2022 renewable target to 175 GW. It was generally accepted from the outset that the new target was more of an aspiration rather than a logical calculation. It is not surprising that actual progress has significantly lagged the targets, but the bold target has nonetheless proved to be a huge draw for the sector. It has provided an overarching vision and helped attract vast amounts of domestic and international capital.

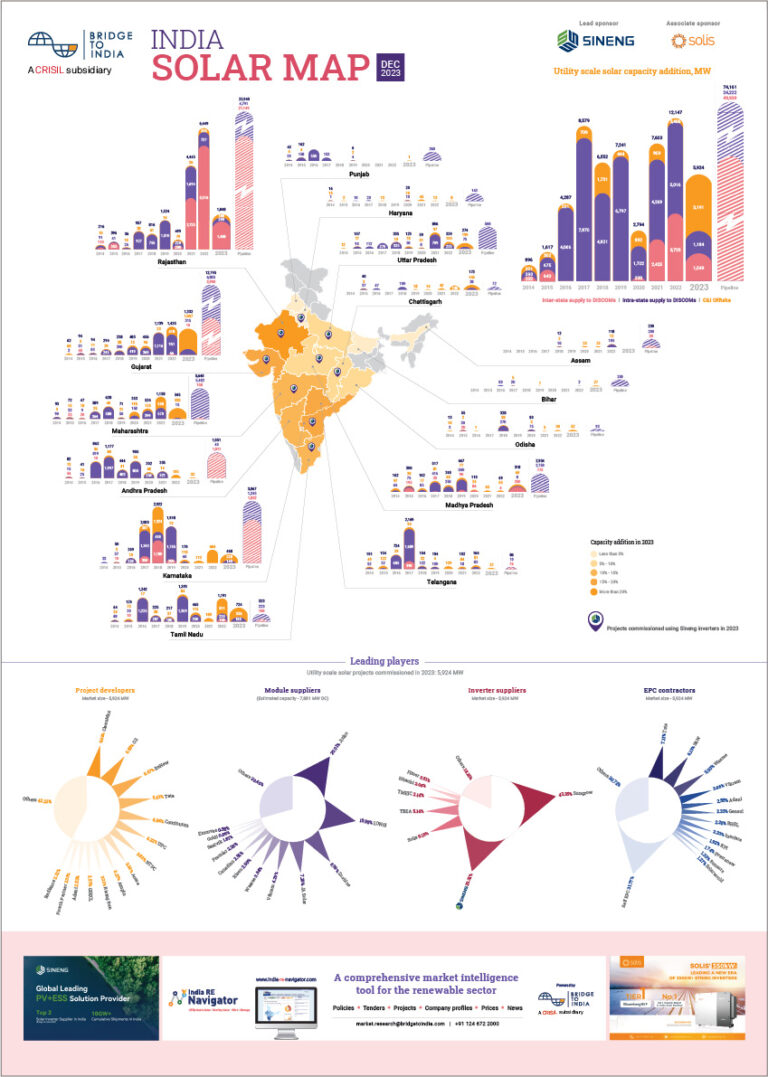

The ambitious target was quickly followed up with a series of very positive and decisive policy measures tackling different facets of the sector – UDAY (DISCOM finances), government solar park scheme (land and transmission connectivity), ‘Power for All’ (power demand) and DCR (domestic manufacturing). There was a huge wave of optimism around the sector with concrete on-the-ground progress. Solar and wind capacity addition rose steadily year-on-year until 2017. Indeed, solar sector added more capacity in 2018 than all other sources combined.

Figure: Power generation capacity addition, MW

Source: BRIDGE TO INDIA research, CEA

Notes: 2018-19 numbers are preliminary estimates. Thermal capacity addition numbers are stated net of retirements.

The other notable success of this government has been the scheme to provide grid power connectivity to every single household in the country. Progress on the SAUBHAGYA scheme has been impressive laying foundation for higher electrification of the economy.

But there have been many terrible disappointments on the way. Around 2017, things began to go awry. Safeguard duty, quality standards and GST were botched creating confusion and increasing costs for the entire supply chain. Slow progress on solar park scheme and transmission network expansion led to undersubscribed tenders and execution delays. Domestic manufacturing remained an elusive goal. The vital electricity sector reform made almost no progress. DISCOM financial position started deteriorating again, as the elections approached, resulting in critical payment delays. Needless damage was caused by arbitrary tariff ceilings and tender cancellations. Taken together, these measures have drained confidence and forced many small-mid size players out of the sector.

On a more macro note, the two biggest failures have been: 1) failure to exploit distributed and off-grid potential of solar – focus on large projects and concentration of capacity in a few states are increasing execution challenges and exacerbating grid management problems; and 2) limited progress on making the power system more resilient (more flexible thermal plants, smart grids, pumped hydro and other balancing resources, ancillary services market, demand side management).

The new government will have its work cut out as the RE sector needs a new vision and a substantial policy reform to pave way for sustained growth.