Gujarat’s new solar policy has severely restricted banking provision for surplus power. Banking shall be available to HT consumers only on a daily basis (residential and LT consumers: monthly basis) and only within specified day hours. The state has also proposed a sharp increase in banking fee to INR 1.10-1.50/ kWh for corporate consumers (previously 2%).

Gujarat joins a growing number of state militating against banking of renewable power. Until three years ago, most states allowed free banking until end of the financial year. But as more consumers seek to procure renewable power independently, DISCOMs and state government agencies are trying to curb the sector by making grid connectivity and banking provisions more onerous (see figure below).

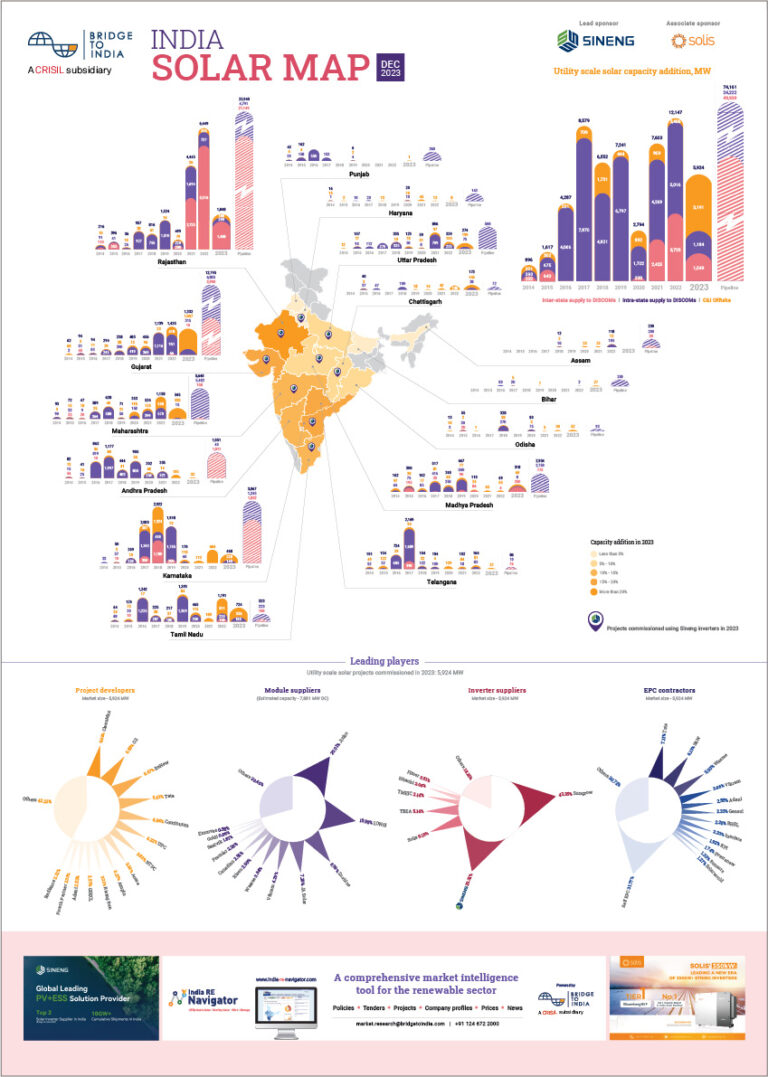

Figure: Banking policies in key sates for C&I renewable power

Source: BRIDGE TO INDIA research

Banking restrictions come mainly in two forms. States are curbing both the amount of maximum power that can be banked as well as period for which power can be banked. While some states like Andhra Pradesh are completely disallowing banking, others like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra now allow banking only for a much shorter period, typically a month. Maharashtra has capped banking at 10% of total generation, while the Joint Electricity Regulatory Commission (jurisdiction Goa and union territories) has proposed to allow banking facility for only 20% of monthly generation. Carry forward of surplus power is allowed to the next billing period, but only if it is below 100 units. Telangana allows carry forward of surplus power only on a half-yearly basis. Haryana allows no banking for third party sale projects. Some states are coming up with novel ways to curb banking. For instance, Punjab allows banking for open access projects only in cases of unscheduled power cuts, which practically means no banking facility for these projects.

Second restriction faced by power producers relates to reduction in compensation for surplus power and/ or levy of banking charges. States are reducing compensation to typically around 75% of average auction tariff or generic tariff (INR 1.50-3.00/ kWh).

Consequently, consumers and project developers are being forced to be more conservative in project sizing to minimise instances of surplus generation. The attempt to cut banking periods and escalate banking charges, together with reversal of net metering and open access incentives, is unfortunately dimming growth prospects of C&I renewable power sector.